- take

downface dog

- put one foot (the corresponding leg becomes the "ankle bone")

with bent knee around approx. thirty centimeters forward and put

most of the weight on this foot.

- Lift the other leg (flybone) off the ground, keep it stretched and swing

it up and down several times in succession.

- On a strong upswing of this leg, decide to jump off with the other leg as well

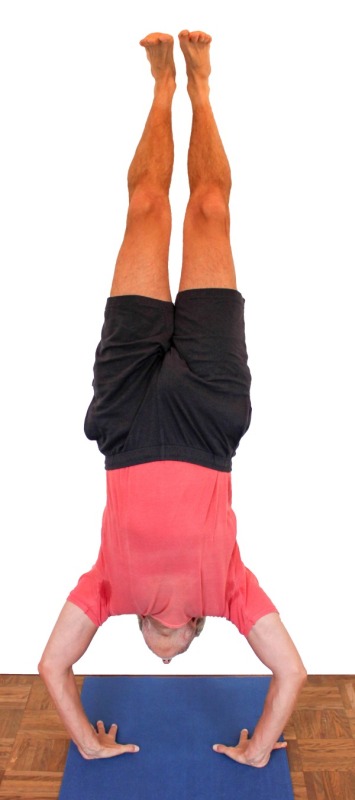

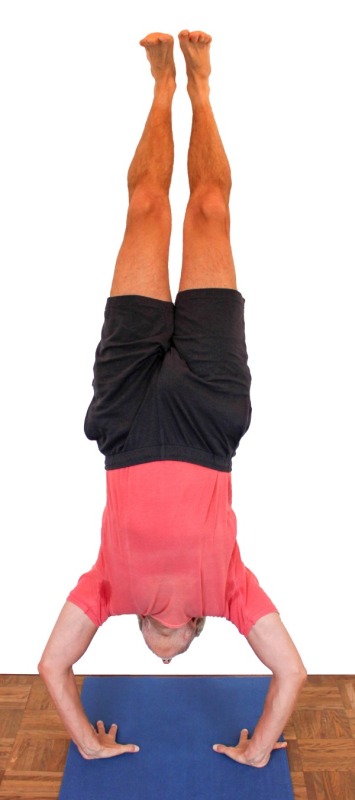

- Stretch from the strength of the arms maximum upwards with a maximum elevation of the shoulder blades (move away from the pelvis)

- keep your shoulders moved away from the wall in every phase,

even if this makes it difficult to take the pose, especially it will aggravate the upswing

|

- For people who are stiff in the back of the leg

(ischiocrural group) it is necessary to warm up these muscles, e. g. with

downface dog or forward bends like

uttanasana, in order to keep the risk of straining as low as possible when the leg swings up strongly.

- Avoid bending the swinging leg when swinging up, which has two drawbacks:

- the momentum that can be achieved with this leg is reduced by bending the leg due to a smaller lever arm

- with bending of the leg, there is a tendency to repel from the wall

when the foot reaches the wall, as with bent legs

the foot usually reaches the wall before the centre of gravity

lies over the hands or between hands and wall

- For beginners, it may be difficult to control the momentum of the pelvis, legs and body

which is transmitted to the shoulder area when jumping up towards the wall,

i. e. it is difficult to keep the distance of the shoulders from the wall large enough

to prevent the head from hitting the wall. Most people have a point of no return:

once the shoulders have crossed a certain point, they are no longer able to return them

and are forced to leave the pose uncontrolled, often frightened and collapsing with

a corresponding risk for the neck and head. Another difficulty that results from this

movement is the decrease of the outer angles in the wrists: sometimes

resulting from the uncontrolled movement of the shoulders angles of dorsal flexion in the wrists occur that exceed the

available degree of flexibility or the amount of bearable force.

- a challenge for many people is the constant, maybe, significant effort in the arms,

especially with fairly inflexible shoulders:

the more inflexible the shoulders are, the greater the tendency to bend the arms,

the more force is therefore required. Stiff shoulders force

- either bending in the arms or

- an insufficient angle between upper arms and upper body.

- endo- insteed of exorotation of the arms

the first two of them cost a multiple of the force required to stand in the handstand.

- A major problem for many people is overcoming the problem of getting

their feet off the ground to stand upside down on their hands.

This clearly shows the influence of psychomental factors on the physical body's performance.

In some cases it may take years for a practitioner to reach handstand

for the first time without assistance, although physiological factors such as

sufficient flexibility and strength have long been given.

Even after one or more times the handstand has been successfully taken alone,

there may still be discontinuities in between,

before it gets almost certain to get into handstand at the first attempt.

- handstand is easier to take and hold by turning your hands outwards.

Note, however, that the stretching and strengthening effect on the shoulder

is less and the necessary balancing changes,

in the sense that it takes a little more attention to balance backwards and forwards,

among other things, because the

support base becomes smaller.

More serious, however, is the fact that with the increasing outward rotation of the hands,

there is fading capability to keep the shoulder and thus the rest

of the body away from the wall by pressing down the palm of the hand

by force of the palmar flexors in the forearm!

Especially beginners must not underestimate this effect but learn by slowly

turning their hands further and further how the pose and

especially the taking changes and can still be taken safely.

- an important movement is stretching from the shoulder (elevation of the shoulder blades), i. e. the exploitation or

expansion of the space in the shoulders, which (if the arms are not in an

over-head position, but next to the body, e. g. in

anatomical zero ) corresponds to the shrugging of the arms, which means the movement of the shoulder blades

in cranial direction (or as a repeated action changing between caudal

an cranial movement). In order to achieve this, one tries,

without changing the angles between legs and pelvis as well as between

upper arms and upper body, to force the muscles needed for

the "shrug of the armpit", mainly the trapezius and levator scapulae,

to push the heels up against the wall, i.e. to translate every effort

of the aforementioned muscles directly into a movement of the heels on the wall

- When a supporter assists you in lifting your legs, note the following:

- the upswinging leg poses a potential hazard to the assistant.

Contact of the swaying foot with the head of the person providing

assistance may cause serious injuries including unconsciousness.

- If the practitioner is helped only on the leg, there is a danger that

the applied force will transfer to the shoulder area of the practitioner and

push the practitioner towards the wall. If the practitioner does not have

the necessary flexibility in the shoulder, or does not have sufficient

orientation as to which movements are necessary, he or she will

turn the applied force into evading the shoulder to the wall

(instead of legs and pelvis further to the wall by increasing the angle

in the shoulders and reducing the angle in the hips) and lose the support

to continue holding on the arms. Therefore, it is necessary for a long

time to limit the range of movement of the shoulder towards the wall,

e. g. by use of a hand or knee.

Furthermore, one of the legs that is pulled up passively causes

torsion and rotation into the upper body and shoulders,

stressing work of the shoulder or the related arm.

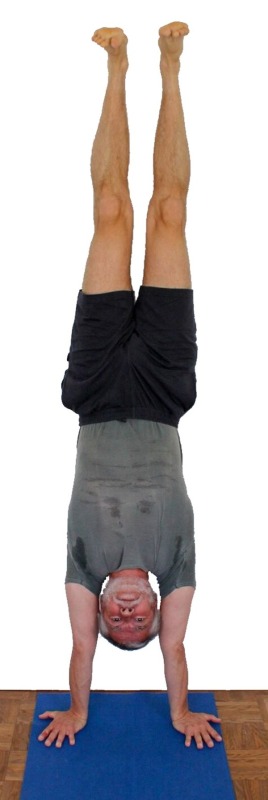

- In the case of people inflexible in the shoulder, there is a tendency to stand in lumbar hyperlordosis

in handstand. This is the result of a significantly smaller angle in

the shoulders than 180°, which prevents the upper body from becoming

vertical (and certainly also from further inclination to the wall).

Since the heels are on the wall, a back arch must be made somewhere between

shoulders and feet. This usually occurs in the lower back area,

since the flexibility of the lumbar spine is unequally greater than that of the thoracic spine,

secondly in most such cases the thoracic spine (which could also be bent back)

will not necessarily be flexible and thirdly the capability of extension (of at least reduction of flexion)

in the hips will usually also not be sufficient.

Often the affected practitioners then leave the handstand with a tense feeling

in the muscles of the lower back, which is however in most cases

harmless and with poses such as

downface dog or, better yet,

1. hip opening

can be removed again quickly. The person providing the support should therefore

also try to increase the angle between upper body and upper arms,

not by simply pressing the upper body towards the wall,

but by applying the same pressure simultaneously holding the shoulder area,

e. g. by holding the shoulders with the hands and pressing the upper body

against the wall via the head in the area of the upper abdominal muscles.

- These factors must be taken into account when practicing with or without assistance.

- The straightening of the upper body, i. e. increasing the angle in the shoulders,

is one of the essential efforts in handstand,

at least until a high degree of shoulder flexibility is achieved.

After that, the focus would be more on stretching from the shoulder or exorotating

the arms. See above for further remarks on how to raise the upper body.

- free handstand is a variant that, correctly executed, in the sense of even pressure

distribution between all metacarpal joints and between these and the wrist area,

will take years of preparation. Here we find extreme relationship between the external

momentum occurring during balancing, resulting from the maximum length

of the lever (here the length from the heel to the wrists) and the available

weight (exactly the total body weight minus only the weight of the hands)

and the means available to cope with it, namely the power multiplied with the

lever arm of the forearm muscles for palmar or dorsal flexion

(this is in the order of 10 cm only).

In addition, many people who are not particularly flexible in the

wrists will find themselves close to the limit of flexibility in the wrists, which is one of the

reasons why they have a markedly reduced strength and performance of the forearm muscles.

As with headstand, it is advisable to try to release slowly and synchronously

from the wall with stretched legs, here - in comparison to the headstand - not only

from the strength of the skeletal muscles and the pressure of the elbows

against the ground from the strength of the shoulder muscles,

but also from the strength of the forearm muscles.

Therefore, it is strongly advised to plan intensive forearm strengthening exercises

as preparation for free standing, as well as to ensure sufficient flexibility

of the wrists and to warm them up sufficiently.

- Even more often than in headstand, it is observed in handstand that the stretched,

swinging leg is bent shortly before reaching the wall, whereby it is guaranteed that a

certain distance of the pelvis from the wall is not deceeded and the centre of gravity is

not shifted sufficiently into the trapezoid of elbows and wrists (in headstand, or between wrists and wall in handstand),

so that the pose is not reached. This should generally be be an unconscious mechanism

designed to prevent control from being withdrawn from the legs and transferred to the arms,

i. e. an expression of fear of the pose and its imponderabilities.

| known issues that may occur even when practicing correctly | - pain in the wrists

occur in many poses in which the wrist is at an angle of about 90°,

e. g. upface dog. In addition to pressing the palm down more forcefully,

palmar forearm stretching helps, it may be possible to place the wrist on

a few patches so that the palm of the hand tilts slightly and the angle

of the necessary dosral flexion is smaller. - Cramping tendency in the trapezius

As with other over-head postures of the arms, there may also be a tendency

to cramp in the trapezius. This is almost always the result of a combination of several factors:

- insufficient flexibility in the shoulder, i. e. the ability

to increase the angle between upper arm and upper body and to

stretch from the shoulder in the sense of shrugging the shoulders.

- a high basic

(tonus) of this part of the

trapezius, possibly combined with low power of this muscle

- insufficient exorotation of the arms or lack of ability to turn outwards

- hollow back pain

if the shoulders are not very flexible, the upper part of the body may stand

significantly tilted against the arms, resulting in a hollow back.

This is, felt and in real terms, the greater the less the attempt

is made to counteract this with the pomusculature. - Cramping tendency in deltoids

Depending on the tension in the trapezius, a tendency to cramp could occur

in rare cases. This would be increased by insufficient exorotation of the arms and

improved by turning them out more vigorously - dizziness

Dizziness usually occurs when leaving handstand, mostly as a result of problems

in the cervical spine or due to circulatory problems as a result of the change

in the circulatory system when leaving handstand: this leads to a deterioration of the

good supply situation of the brain in handstand, which requires a

counter-regulation until the end of which dizziness can occur.

However, this should not last longer than one minute.

If the dizziness lasts longer, the cause is usually more likely

to be found in the cervical spine

|

|